We put excellence, value and quality above all - and it shows

A Technology Partnership That Goes Beyond Code

“Arbisoft has been my most trusted technology partner for now over 15 years. Arbisoft has very unique methods of recruiting and training, and the results demonstrate that. They have great teams, great positive attitudes and great communication.”

US Custom Software Development Contracts & Governance Guide

Custom software projects rarely fail because one clause was “wrong.” They fail when contracts and governance do not translate into clear delivery behaviors: who decides what, how changes are approved, how “done” is measured, and what happens when production support begins.

This guide is a delivery focused way to think about the contract stack and the governance mechanics that keep scope, quality, and ownership predictable. If you are still early in vendor selection, use the broader buyer’s guide to choosing a custom software development partner to make sure contracts fit the engagement model you are choosing.

Why this decision matters: contracts are your operating system for delivery

This section supports one decision: whether your contract stack will actually run the project the way you think it will. The goal is to connect legal terms to day to day delivery, so you can reduce the most common friction points before kick off.

What goes wrong in real life (and why it is rarely “just a legal issue”)

When governance is weak, the problems show up in meetings, tickets, and invoices long before they show up in court. Common breakdowns include:

- Scope drift because backlog changes are treated as “small tweaks” with no impact review

- Acceptance disputes because “done” is subjective, or acceptance testing is not clearly defined

- IP surprises because ownership is unclear for custom code versus vendor background components

- SLA misfit because service level terms are attached to build work where metrics are hard to measure

None of these are purely legal problems. They are operating problems. The contract stack is the operating system that determines which conversations happen early, which decisions are documented, and how disputes are resolved when pressure rises.

The contract stack in one sentence

Use this sentence to align stakeholders fast:

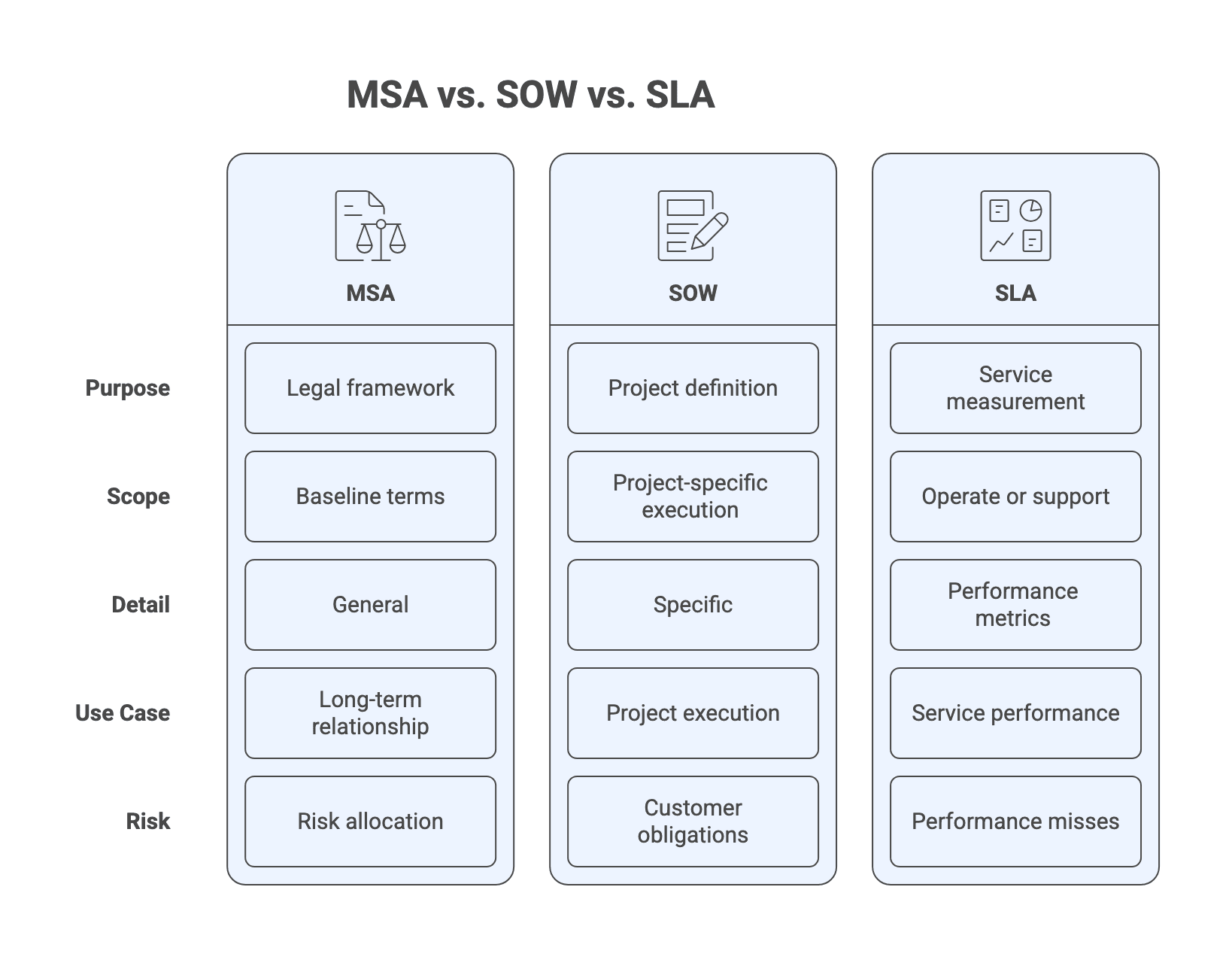

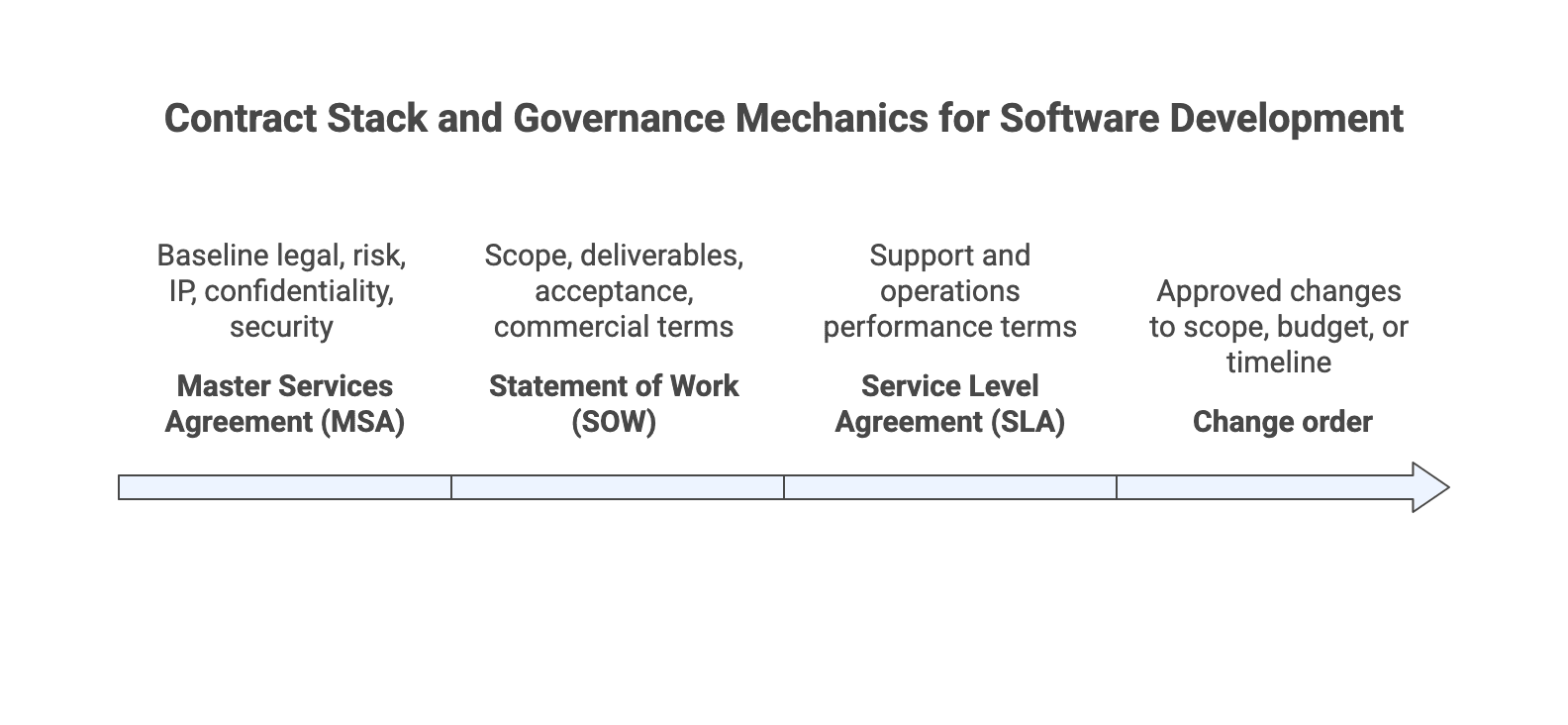

The Master Services Agreement (MSA) sets the baseline legal and risk terms, the Statement of Work (SOW) defines what you are building and how acceptance and payment work, any Service Level Agreement (SLA) governs ongoing support and operations, and change orders document approved scope, budget, or timeline changes so delivery tools and invoices stay consistent.

Definitions and key concepts: MSA, SOW, SLAs, acceptance, change requests

This section supports a practical negotiation decision: are you using the same words the vendor uses, and do those words map to the right document? Misaligned definitions are a reliable source of later disputes.

Master Services Agreement (MSA): what it should do and what it should not do

An MSA is a baseline agreement. It should establish the legal framework for the relationship: risk allocation, confidentiality, intellectual property boundaries, security obligations, and how disputes are handled.

What it should not do is attempt to describe the entire project. When an MSA tries to carry project scope, milestones, or acceptance detail, it tends to become either too vague to enforce or too rigid to support iterative delivery. The better pattern is: stable baseline terms in the MSA, project specific execution detail in each SOW.

Statement of Work (SOW): the executable definition of “done”

A SOW is the project’s executable definition of “done.” It is where scope boundaries, deliverables, assumptions, acceptance criteria, and commercial terms become specific enough to run delivery and invoicing.

A useful SOW also makes customer obligations explicit. Many delivery issues come from missing inputs, delayed access, or unclear decision rights. If responsibilities are not written down, they are often “discovered” during escalation.

Service Level Agreement (SLA): when it applies vs when it is a distraction

An SLA is most valuable when the engagement includes operate or support. It becomes the mechanism for measuring service performance in production: availability, response times, resolution times, and remedies when performance misses targets.

An SLA can be a distraction when it is attached to build work where metrics are hard to measure objectively. In those cases, a warranty period, support terms, and clear acceptance criteria often do more to reduce disputes than forcing SLA style metrics onto a development phase.

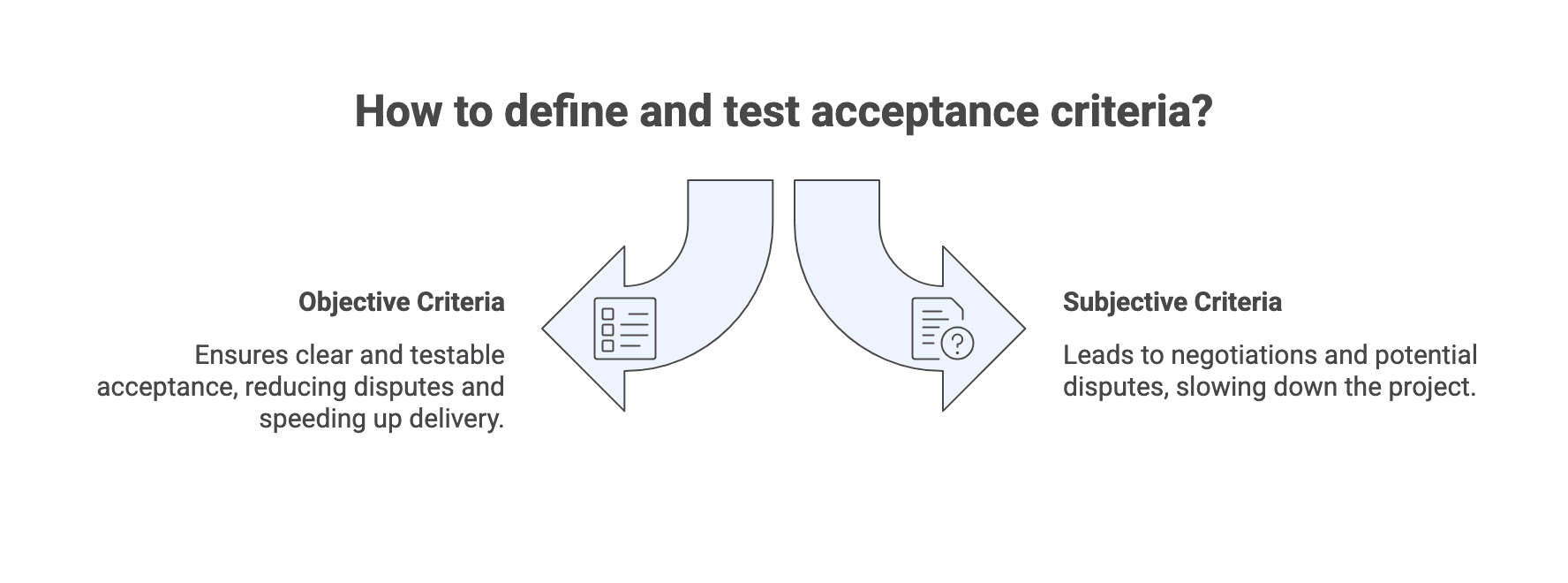

Acceptance criteria and acceptance testing

Acceptance is where scope and payment meet. Acceptance criteria define what “done” means for a deliverable, and acceptance testing defines how that determination is made.

A practical approach is to keep acceptance objective and testable. If acceptance relies on subjective judgment, it becomes a negotiation every time a milestone is reached. That slows delivery and increases the likelihood of invoice disputes.

A simple acceptance mini template you can reuse in a SOW:

- Deliverable name and description

- Acceptance tests or measurable criteria

- Test environment and data assumptions

- Acceptance window and review process

- Defect severity rules and re testing cycle

- What triggers final acceptance and payment

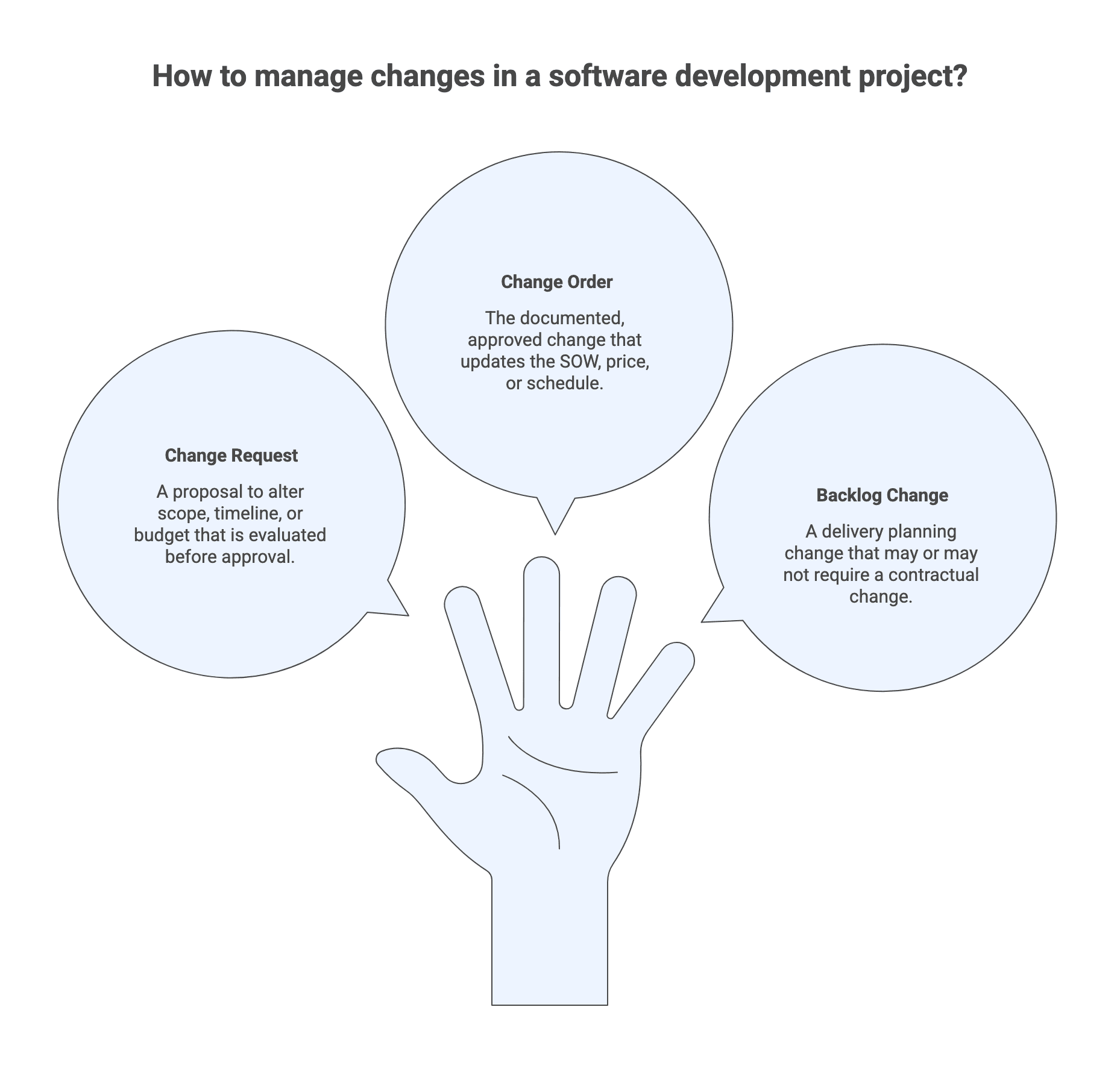

Change request vs change order vs backlog change

These terms are easy to mix up, and that confusion causes process breakdowns.

- A change request is a proposal to alter scope, timeline, or budget that is evaluated before approval.

- A change order is the documented, approved change that updates the SOW, price, or schedule.

- A backlog change is a delivery planning change. It may or may not require a contractual change depending on impact and agreed thresholds.

The core governance goal is to define when a backlog change becomes a contractual change. That boundary is where many projects either maintain trust or start accumulating friction.

How the contract stack works together: document hierarchy and governance mechanics

This section supports one decision: do your documents and governance mechanics prevent conflicts, or do they create ambiguity when priorities change? The focus is on order of precedence, decision rights, and the minimum artifacts that keep everyone aligned.

Document hierarchy and order of precedence

Order of precedence prevents “which document wins” debates. Without it, teams can end up arguing whether the SOW overrides an exhibit, whether security terms live in a separate addendum, or whether a later statement in email changes obligations.

A practical hierarchy usually makes the MSA the baseline, then allows SOWs and approved change orders to control project specifics. Security addenda and other exhibits need explicit placement in that hierarchy so project teams do not discover conflicts after signature.

Here is a compact way to sanity check the stack before you sign:

Document | Primary job | Typical owner | What to verify |

| Master Services Agreement (MSA) | Baseline legal, risk, IP, confidentiality, security | Legal, procurement | Clear order of precedence and no conflicts with SOW or addenda |

| Statement of Work (SOW) | Scope, deliverables, acceptance, commercial terms | Delivery leadership | Objective acceptance criteria and explicit assumptions |

| Service Level Agreement (SLA) | Support and operations performance terms | Ops, support | Metrics are measurable and aligned to monitoring sources |

| Change order | Approved changes to scope, budget, or timeline | Governance forum | Updates both the SOW and the delivery backlog mapping |

Treat the table as a reading checklist. If any row is unclear, you are likely to see that same confusion later in status meetings.

Governance model: who decides what, how often, and with what inputs

Governance is not a slide deck. It is decision rights plus cadence plus evidence.

A working governance model typically clarifies:

- Who owns business outcomes and priority decisions (often a business owner or executive sponsor)

- Who owns backlog priorities and scope trade offs (often a product owner)

- Who owns delivery commitments and delivery reporting (often a delivery lead)

- How decisions are escalated when there is a schedule, budget, or scope conflict

- What inputs are required before approving a change, accepting a milestone, or escalating a dispute

Even if you are running agile delivery, governance still needs a formal path for decisions that have contractual impact. When governance is informal, scope and payment disputes tend to become personal and slow.

The minimum artifact set that makes governance real

Governance requires artifacts that preserve decisions and reveal cumulative impact. A minimum set often includes:

- Decision log: what was decided, when, by whom, and why

- RAID log: risks, assumptions, issues, dependencies (RAID) and ownership for each

- Roadmap and milestone plan: how work will be sequenced and validated

- Backlog rules: who can add or change items, and what triggers a formal change request

- Status reporting: cadence, format, and escalation thresholds

The goal is traceability instead of paperwork. When scope or quality debates happen, you want a shared record of decisions and assumptions, rather than a reconstruction from chat history.

What to negotiate and verify in the MSA (high-impact terms that affect delivery)

This section supports a negotiation decision: which MSA terms will materially affect delivery outcomes, and what should you verify before relying on them.

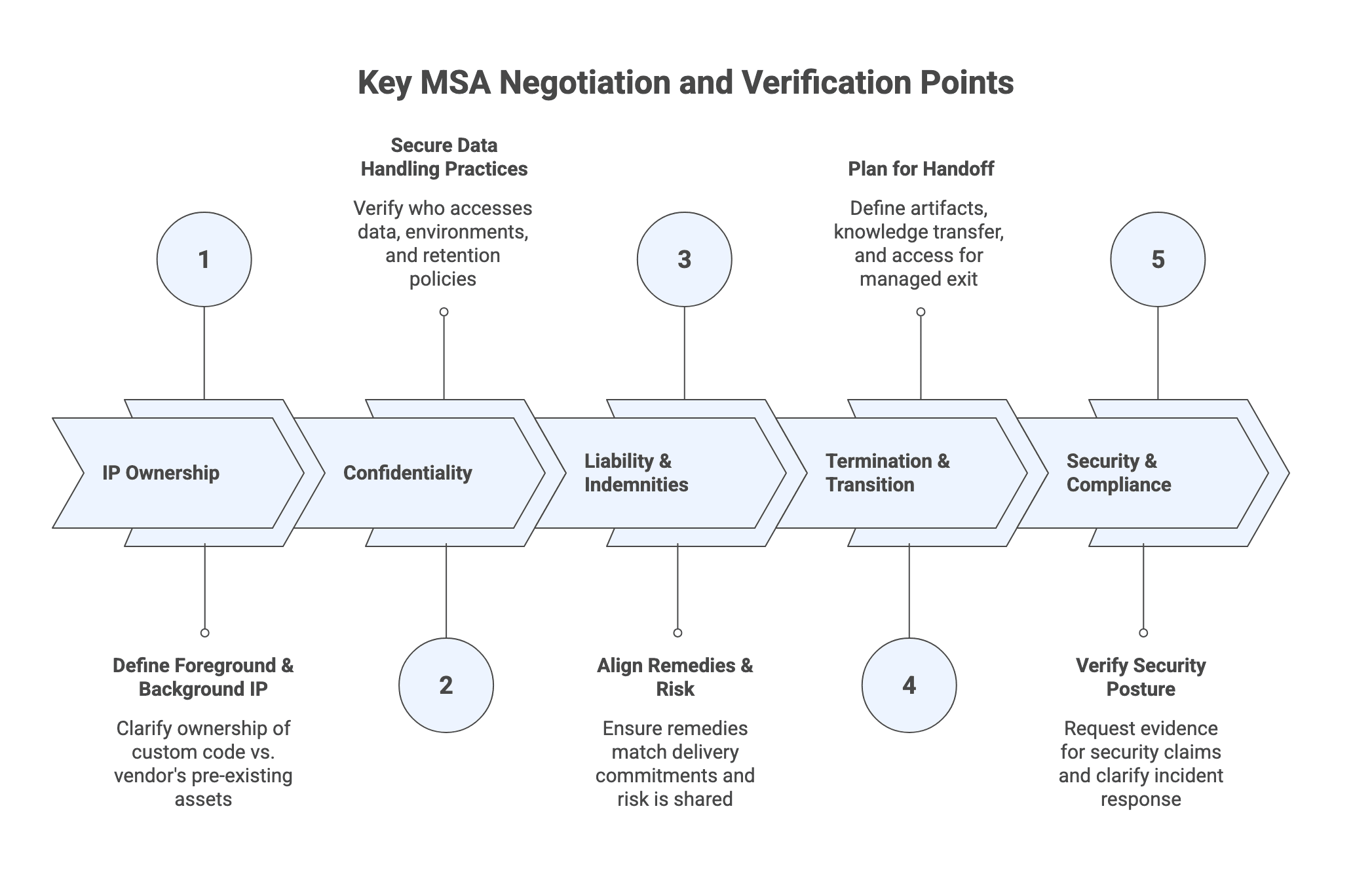

IP ownership, background IP, and licensing boundaries (MSA level)

Intellectual property (IP) terms define what you will own, what you will license, and what you may be dependent on later.

A common pattern is to distinguish foreground IP from background IP:

- Foreground IP is work product created specifically under the contract.

- Background IP is the vendor’s pre existing tools, code, and know how.

Buyer friendly defaults often assign ownership of foreground IP to the customer while allowing the vendor to retain background IP. In practice, contracts may assign rights for custom code but grant licenses for embedded vendor components.

What to verify in practical terms:

- The definitions capture your real “custom” value

- Any vendor license is perpetual or long enough to avoid future lock in

- The SOW deliverables description matches the IP allocation, including items like deployment pipelines, infrastructure as code, and configuration scripts when they are essential to operate what you are buying

Confidentiality and data handling (including subcontractors)

Confidentiality determines how your data can be used and who can access it.

Typical confidentiality provisions require each party to protect the other’s confidential information, use it only for contract purposes, and limit disclosure to personnel and contractors with a need to know. Data handling terms often include requirements for return or destruction of information at the end of the engagement.

A practical verification approach:

- Confirm who will have access to your data, including subcontractors

- Confirm what environments will be used for development and testing

- Confirm what happens to your data and credentials when the engagement ends

If these questions feel operational, that is the point. Confidentiality only works when it maps to real access and retention practices.

Liability, indemnities, and warranties (what they mean operationally)

Many buyers treat liability and indemnity as abstract legal clauses. Operationally, they determine what remedies are realistic when something goes wrong and how risk is shared.

At a practical level, you want alignment between:

- The remedies available for failures (including any SLA remedies, if applicable)

- The limitation of liability structure in the MSA

- Any termination rights and transition support obligations

If the contract promises remedies that are later limited or excluded elsewhere, you can end up with rights that look strong on paper but are hard to exercise. The best use of this section is to make sure legal terms do not undermine the delivery and support commitments you are relying on.

Termination, transition assistance, and handover obligations

Termination is a predictable event when priorities shift, budgets change, or you switch vendors.

Transition assistance and handover obligations are what turn termination into a managed transfer instead of a scramble. Practical handover topics include:

- What artifacts must be delivered at handoff (code, documentation, environment configuration)

- What knowledge transfer is included and how it is scheduled

- What access is required for your team to keep operating and maintaining the system

If you cannot operate what you paid for without ongoing vendor involvement, you have created dependency risk. Addressing transition mechanics early is one of the simplest ways to reduce that risk.

Security addendum, audit rights, and compliance claims

Security obligations often live in a security addendum or exhibit. The core governance question is whether security requirements are specific, testable, and backed by evidence.

A structured approach is to treat compliance claims as verifiable statements. If a vendor claims a security posture or certification, the pre sign step is to request evidence that the claim is current and relevant to the services you are buying.

Operationally, clarify:

- Incident response expectations and communication cadence

- What security documentation you will receive

- How security requirements flow into delivery practices and tooling

Security clauses that cannot be verified tend to become arguments after an incident.

Writing a SOW that protects schedule, budget, and quality

This section supports a drafting decision: can your SOW be executed without constant renegotiation? The focus is on scope boundaries, deliverable definition, acceptance, and aligning commercial terms to the delivery model.

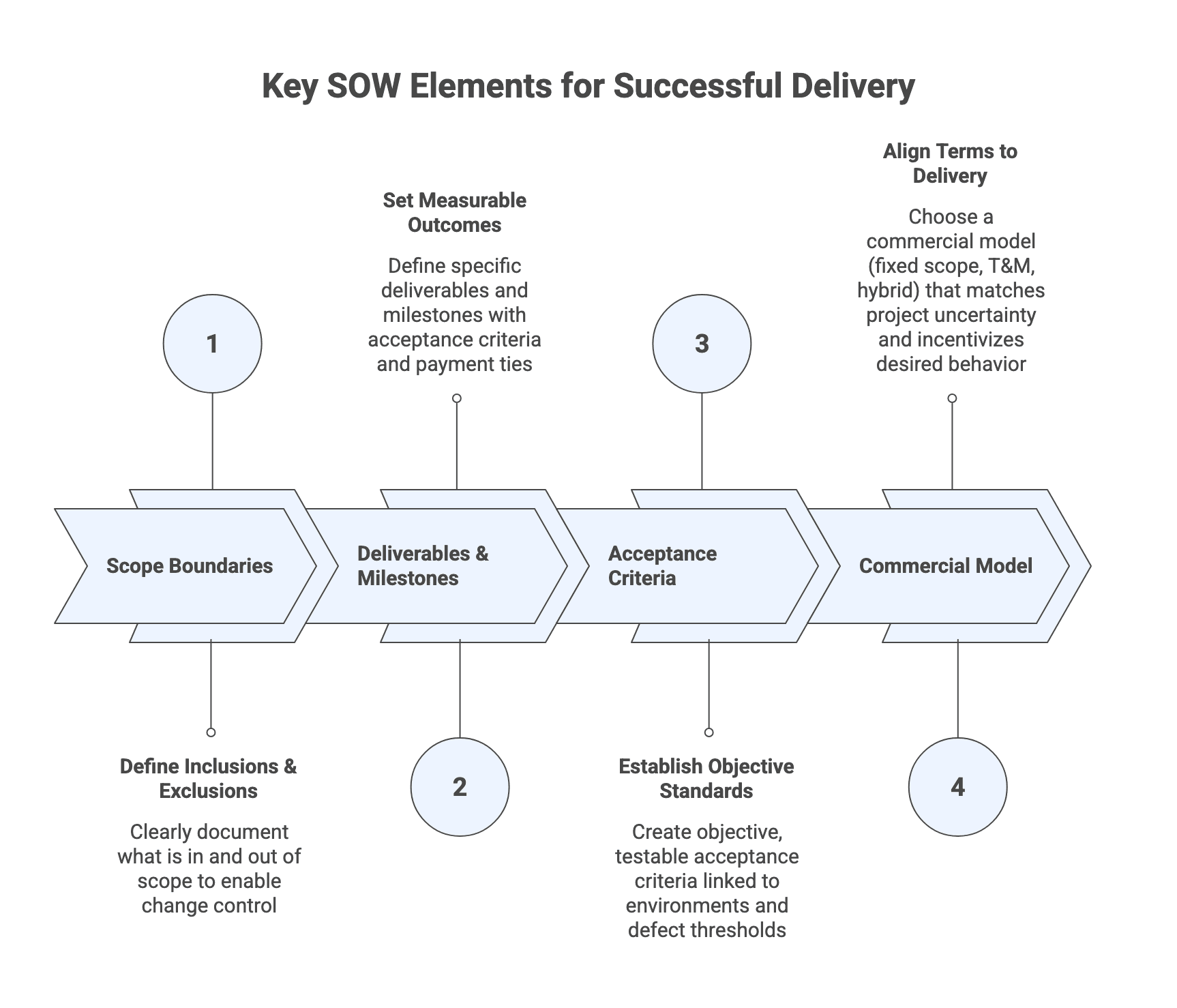

Scope boundaries, assumptions, and exclusions (so change control is workable)

Scope boundaries are what make change control possible. If scope is vague, every discussion becomes a debate about whether something was “included.”

A workable SOW makes assumptions explicit and exclusions clear. That gives both sides a shared reference point when priorities change or new requirements emerge.

To keep this practical, aim to document:

- What is in scope at the level of features, outcomes, or epics

- Key assumptions and dependencies (access, data, stakeholder availability)

- Explicit exclusions and what would trigger a change request

Deliverables, milestones, and acceptance windows (tie to payment)

Deliverables and milestones only protect you if they connect to acceptance and payment. Otherwise, you can end up paying for activity rather than outcomes.

When milestones exist, define:

- What is delivered at each milestone

- What documentation or deployment artifacts are included

- How long the acceptance window lasts and what happens if defects are found

- Whether partial acceptance exists for phased delivery

The goal is to avoid the classic argument where one side believes a milestone is complete and the other side believes it is “nearly done.”

Acceptance criteria design (objective, testable, and linked to environments)

Acceptance becomes subjective when environments, data, and test responsibility are unclear.

To keep acceptance objective:

- Define acceptance tests or measurable criteria per deliverable

- Specify the environment where acceptance occurs and who provisions it

- Clarify what “passed” means, including defect severity thresholds

- Define the re testing loop so acceptance does not stall indefinitely

If you only take one action from this section, make acceptance criteria explicit enough that a neutral third party could understand what “done” means.

Commercial model alignment: fixed scope, T&M, managed capacity, hybrid models

Commercial terms shape behavior. If the commercial model rewards output volume rather than outcomes, you should expect more scope churn and more disputes.

Common models include:

- Fixed scope: can work when requirements are stable and acceptance is objective

- Time and materials (T&M): flexible, but needs strong governance to prevent backdoor scope

- Managed capacity: a dedicated or semi dedicated team capacity model, often paired with evolving scope

- Hybrid: used to create stability on one dimension (budget or timeline) while keeping controlled flexibility on scope, often combined with explicit change control and re baselining triggers

The key is to match the model to uncertainty. If scope is likely to change, the SOW should make change control and estimation discipline explicit rather than pretending the scope is fully known.

SLAs and service governance (only if your engagement includes operate/support)

This section supports a scoping decision: do you need an SLA now, and if so, is it measurable and enforceable? If you are only building, focus first on acceptance and warranty terms.

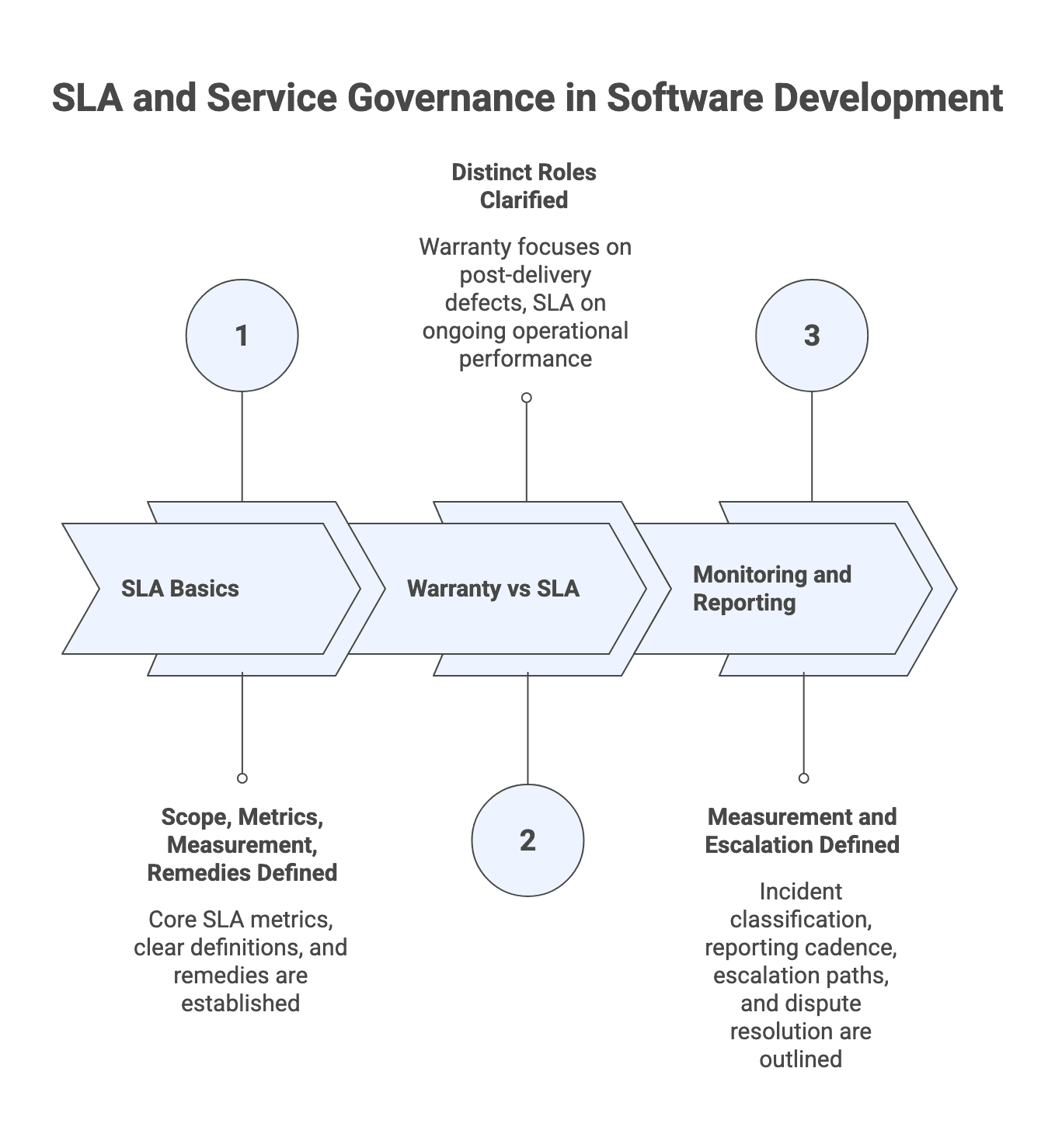

SLA basics: scope, metrics, measurement, remedies

Core SLA metrics in software and cloud services commonly include availability, response time, resolution time, performance measures, and error rates. For these metrics to be useful, definitions must be clear: what counts as downtime, what time basis applies, and how maintenance windows are treated.

Remedies often include service credits, but credits are frequently small relative to business impact. The operational value is usually in performance motivation and clear escalation expectations. Practical remedies can also include enhanced support, root cause analysis, corrective action plans, and in severe or repeated breaches, termination rights.

The most important governance move is to confirm that metrics are measurable with the monitoring and support systems you will actually use, and that both parties agree on the data source.

Warranty vs SLA: avoiding the "SLA for build" trap

A warranty period and an SLA solve different problems.

- Warranty focuses on post delivery defect correction for what was built and accepted.

- SLA focuses on ongoing operational performance and support response.

Trying to force SLA style metrics onto build work can create arguments about measurement rather than improving quality. If your engagement does not include operate or support, you may get better outcomes by tightening acceptance criteria, clarifying warranty scope, and defining support terms for the stabilization period.

Monitoring and reporting: who measures and how disputes are resolved

SLAs only work when measurement is agreed and reporting is routine.

A practical approach includes:

- A clear definition of how incidents are classified by severity

- A defined reporting cadence and what is included in reports

- A clear escalation path during major incidents, including management involvement

- A dispute resolution approach for measurement disagreements, so arguments do not stall remediation

Before you rely on SLA terms, verify the vendor can demonstrate how reporting and escalation work in practice.

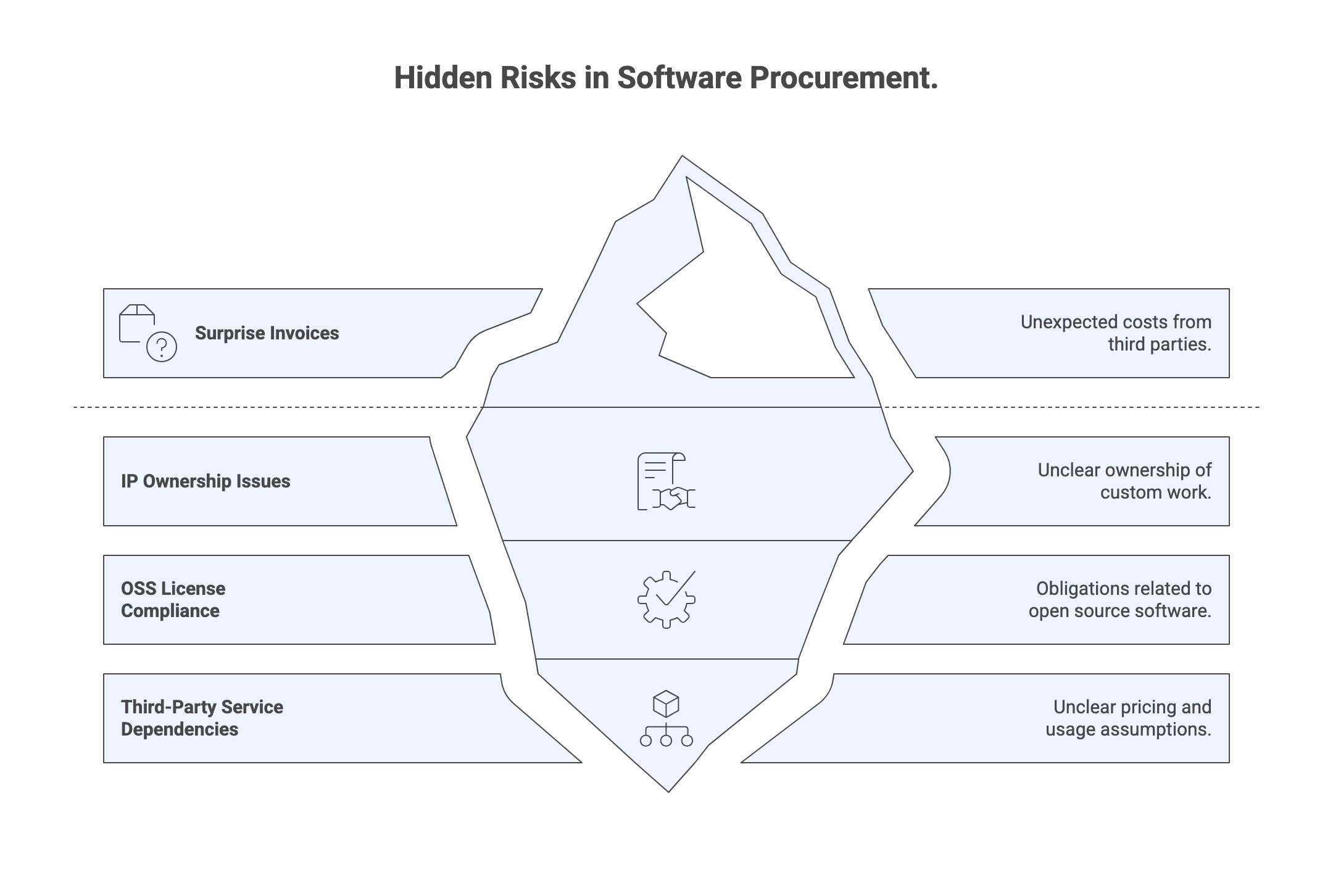

IP and third-party software: avoid surprises in ownership and OSS

This section supports an ownership and dependency decision: will you be able to use, maintain, and evolve what you are buying without hidden licensing or third party constraints?

Foreground vs background IP: what “buyer-friendly” looks like in practice

Foreground versus background IP is only useful if it maps to the deliverables you need to operate the system.

Buyer friendly patterns often look like:

- You own the custom work product created for the engagement

- The vendor retains pre existing tools and reusable components

- Any embedded vendor components are licensed in a way that does not create future lock in

The practical verification step is to review whether the deliverables list in the SOW includes the operational artifacts you will need. If an item is essential to operate or redeploy the system, confirm it is part of the work product you receive.

Open source software (OSS) and SBOM: governance that prevents future risk

Modern applications often rely heavily on open source software (OSS) and third party services. That can be a strength, but it also introduces license compliance and security obligations.

A robust approach includes:

- An OSS policy and approval workflow

- Transparency on third party components and costs

- A software bill of materials (SBOM) listing open source and third party components, including versions and licenses

Contracts can also define which licenses are acceptable, require prior approval for certain copyleft licenses, and obligate the vendor to address security vulnerabilities in included components.

If you want one concrete outcome, request a sample SBOM and the vendor’s OSS policy as part of pre sign verification.

Third-party services and pass-through costs: avoid “surprise invoices”

Third party services can create cost and dependency risk when pricing or usage assumptions are unclear.

To reduce surprises:

- Require transparency on which third party services are used

- Clarify which costs are included versus passed through

- Connect third party usage assumptions to your governance process, so new services are not introduced without review

This is less about controlling every tool choice and more about maintaining budget predictability and reducing hidden dependencies.

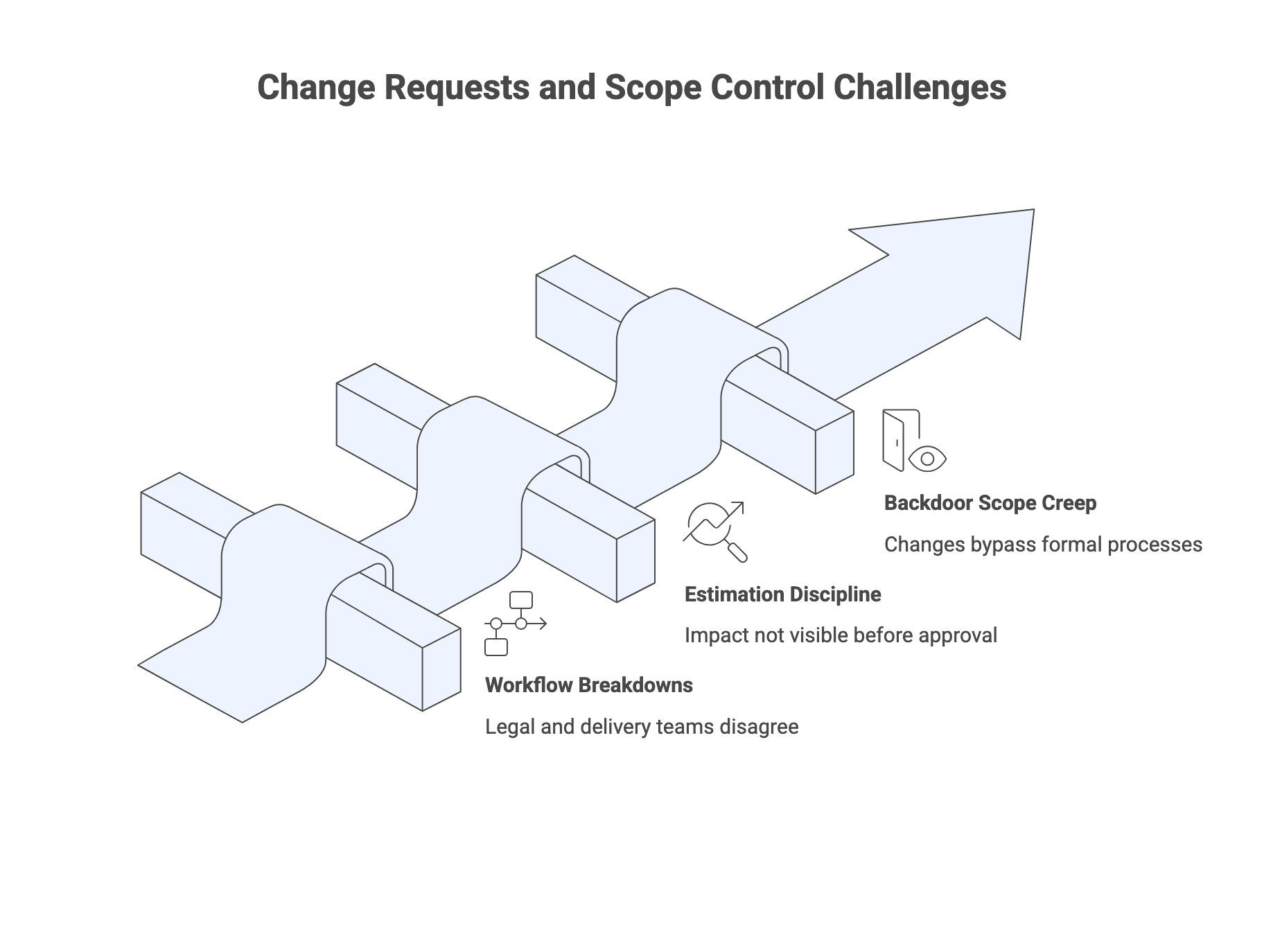

Change requests and scope control: a process that does not break budget or trust

This section supports one operational decision: how will changes be evaluated, approved, and documented so the backlog, the SOW, and invoices stay aligned?

A simple change request workflow that both legal and delivery teams can live with

A workable change workflow is lightweight but explicit.

A typical pattern:

- Submit change request with description, rationale, and urgency

- Triage and classify: is it a contractual change or a backlog change within agreed bounds?

- Estimate impact on cost, timeline, and risk

- Apply approval thresholds (bigger changes require higher level approval)

- Once approved, issue a change order that updates the SOW, budget, or timeline

- Reflect the approved change in the backlog and roadmap so delivery tools match the contract

The key is to avoid a split brain where the contract says one thing and the backlog says another.

Estimation discipline: make impact visible before approval

Estimation is uncertain, but you can reduce avoidable surprises.

Useful practices include:

- Present estimates as ranges with stated confidence levels

- Break work into smaller tasks and list assumptions and dependencies

- Define re baselining triggers so small changes do not accumulate into major drift

- Challenge estimates with comparable historical examples and alternative options, such as a minimal viable change versus a full feature

Over time, review actuals versus estimates in governance forums. That feedback loop improves estimation quality and builds trust.

Preventing "backdoor" scope creep: align governance to delivery tools

Backdoor scope creep happens when changes bypass formal processes through informal agreements, chat messages, or quick tweaks added to sprints without re evaluating impact. This is especially common in flexible delivery models where backlog items change frequently.

Prevention is mostly rules and traceability:

- Define who can add or change backlog items

- Define when a new or changed item requires a formal change request

- Map contractual scope to backlog epics or features so it is visible when you are leaving scope

- Use decision logs and RAID logs to track scope related decisions and cumulative impact

A strong sign of maturity is a vendor who can demonstrate these mechanisms from prior engagements.

Practical verification steps before you sign

This section supports a readiness decision: do you have evidence that the vendor operates with the delivery discipline, security posture, and governance maturity the contract assumes?

What to request from the vendor (artifact checklist)

Contracts encode intentions, but artifacts show how work is actually run.

A practical pre sign artifact set can include:

- Sample or template MSA and SOW

- Sample change request and change order

- Example status reports and RAID logs

- Security and data handling documentation

- Standard SLAs for support services, if offered

- Recent SLA performance reports and incident post mortems for ongoing services, anonymized as needed

- Sample SBOM and OSS policy for prior work

Reviewing these with internal stakeholders (legal, IT, security, operations) often reveals misalignment that would not be visible in marketing material.

Red flags that predict future disputes

Certain patterns correlate strongly with future friction. Watch for:

- Vague or missing acceptance criteria

- No clear order of precedence

- SLAs attached to build work where metrics are hard to measure

- Unclear or one sided IP ownership

- Weak or absent governance and escalation description

- No evidence of structured change control

If you see multiple red flags, the likely outcome is repeated renegotiation during delivery.

Negotiation prep: align internal stakeholders before redlining

Many contract delays are internal, rather than vendor driven.

Before heavy redlining, align on:

- Your non negotiables (IP outcomes, security posture, acceptance rigor, change control)

- Your preferred engagement model and how commercial terms should shape behavior

- Who has decision authority and what approvals are required internally

- What evidence you need from the vendor to be comfortable signing

You do not need perfect alignment to start negotiation, but you do need a shared definition of success and the risks you will not accept.

Conclusion: governance is the difference between “signed” and “successful”

A strong contract stack does not guarantee success, but it reduces the most predictable failures: unclear scope boundaries, subjective acceptance, hidden IP dependencies, and unmanaged changes.

The practical goal is simple: make sure the MSA, SOW, any SLA, and the change process form a single operating model. If the documents align and the governance artifacts exist, you can spend status meetings shipping software, instead of renegotiating what was meant.

For the full content cluster on selecting and managing a partner explore our custom software vendor selection hub.