We put excellence, value and quality above all - and it shows

A Technology Partnership That Goes Beyond Code

“Arbisoft has been my most trusted technology partner for now over 15 years. Arbisoft has very unique methods of recruiting and training, and the results demonstrate that. They have great teams, great positive attitudes and great communication.”

Managing Scope Creep in Custom Software Development: Change Requests That Don’t Break Budget

Scope creep is not usually a surprise. It is the predictable outcome of unclear baselines, fuzzy definitions of “small change,” and decisions made in side channels that never hit a change log. The good news is that you do not need a heavy bureaucracy to control it. You need a shared vocabulary, a simple workflow, and a few budget guardrails that make trade offs explicit.

Why scope creep happens

Scope creep typically starts before the first formal change request (CR). Common patterns include:

- Ambiguous scope definitions that invite interpretation during implementation

- Weak requirements management and unclear acceptance criteria

- Low stakeholder involvement early, followed by late feedback during demos and QA

- Fragmented communication, with decisions made in chat threads, calls, or emails that never become tracked work

Where budget leaks start is often in “clarifications” that quietly alter behavior. A product owner tweaks acceptance criteria after development begins. A subject matter expert asks for “one more thing” while a developer is already in the code. Teams feel ahead of schedule and say yes without logging the ripple effects.

Early warning signals you can spot quickly:

- Reopened tickets in QA because “what we meant” changed

- Rising volume of urgent tweaks after demos

- Stakeholders referencing undocumented needs as if they were already agreed

- Vendor estimates that only mention build effort and skip testing, release, and risk

A practical vendor maturity test: ask to see how they define scope vs change, and what artifacts they maintain to log and assess changes. If they cannot show a consistent mechanism, scope creep is not a risk. It is the default outcome.

Definitions that prevent arguments later

Most scope disputes are classification disputes. One side calls it a bug. The other side calls it new scope. Clear definitions make the conversation objective and reduce the “free work” drift that breaks budgets.

Scope vs requirements refinement vs defects

Use these criteria to classify requests:

- Scope change: Introduces new capability or materially changes behavior beyond what was agreed.

- Requirements refinement: Clarifies an already agreed requirement without changing its intent.

- Defect: The delivered behavior does not match the agreed baseline requirement or acceptance criteria.

Gray zones usually come from vague requirements. When the baseline is unclear, teams misclassify usability improvements as defects or treat real defects as scope. The remedy is traceability: every request should map back to a baseline artifact such as a requirement, user story, acceptance criteria, or a documented assumption.

CR intake and classification rubric (use this every time)

Classify a request as a scope change if any of the following are true:

- It adds a new workflow, role, permission, integration, report, or data object

- It changes a decision rule in a way that alters outcomes for users

- It requires new screens, APIs, schema changes, or additional non functional requirements

Classify a request as refinement if all of the following are true:

- The underlying intent already exists in the baseline

- The change clarifies edge cases or validation rules implied by the baseline

- The work is mostly specification and acceptance criteria tightening

Classify a request as a defect if all of the following are true:

- The baseline explicitly states the expected behavior

- The delivered behavior deviates from it

- Fixing it restores the agreed behavior rather than adding a new one

A vendor that can walk you through real examples across these buckets tends to have healthier scope control.

Baseline scope, assumptions, and “definition of done”

A baseline scope is the reference point that makes change control fair. In custom software, it is usually represented by a Statement of Work (SOW), a requirements set or initial product backlog, plus clear exclusions.

Two baseline additions reduce later conflict:

- Assumptions log: What both sides are taking for granted about data, integrations, access, user roles, and dependencies. If an assumption proves false, you can treat the resulting change as a risk realization.

- Definition of done: What “complete” means for development, testing, documentation, and release readiness. A strong definition of done reduces rework and prevents endless reopening of “done” items.

What to insist on at kickoff:

- Baseline scope list with exclusions

- Acceptance criteria patterns for user stories or features

- Definition of done that includes testing and release steps

- Assumptions log tied to the RAID log (Risks, Assumptions, Issues, Dependencies)

Change request (CR) vs backlog item vs enhancement

A CR is a governance artifact that proposes a change to baseline scope, schedule, or budget, with impact assessment and approvals.

In agile delivery, backlog items are the units of planned work. Not every backlog change needs a CR. The key distinction is whether the change alters the underlying agreement.

Practical mapping:

- Defects: defect tickets, corrected to meet baseline

- Refinements: updates to existing backlog items and acceptance criteria

- Scope extensions: CRs that may generate new backlog items and update the baseline

Enhancements are usually scope extensions, especially when they add value beyond the baseline. Treat them as CRs unless they are already covered by an agreed change budget envelope.

The budget impact mechanics of change requests

A CR affects the budget through three channels:

- Direct effort to design and build the change

- Rework of already completed work

- Coordination overhead across stakeholders, teams, and release processes

These costs compound when changes are frequent and unmanaged. The finance friendly move is to force visibility: each CR should show cost, timeline, risk, and value in plain language.

Why “just one more feature” is rarely just one thing

Even a small feature change can touch multiple areas:

- Analysis and UX

- Data model and APIs

- Security and permissions

- Testing and regression coverage

- Deployment, monitoring, and documentation

A simple example is a new field on a form. That single field can require database updates, API changes, validation rules, UI updates, accessibility checks, and additional regression tests. If impact assessments do not enumerate these workstreams, estimates are often understated.

The two multipliers: rework and coordination overhead

Rework is the multiplier when changes force revisiting completed work: redesign, refactor, retest, and re document.

Coordination overhead is the multiplier from reviews, approvals, meetings, cross team alignment, and release planning.

These multipliers grow with:

- Late changes after design decisions have hardened

- Many changes hitting the same module, causing conflicts and repeated testing

- Unclear ownership and side channel decisions

A useful question to add to every impact assessment: “How much completed work must be revisited?” That makes the rework multiplier visible.

When scope creep turns into schedule creep (and then cost creep)

Scope creep often presents first as schedule volatility: milestones slip, sequencing changes, and teams lose the ability to forecast reliably. Once the timeline extends, costs usually follow: more labor hours, more overhead, and higher exposure to external changes like stakeholder turnover or shifting requirements.

The guardrail is simple: if scope increases, either schedule changes, budget changes, or other scope is swapped out. If none of the three is allowed to move, quality becomes the hidden variable.

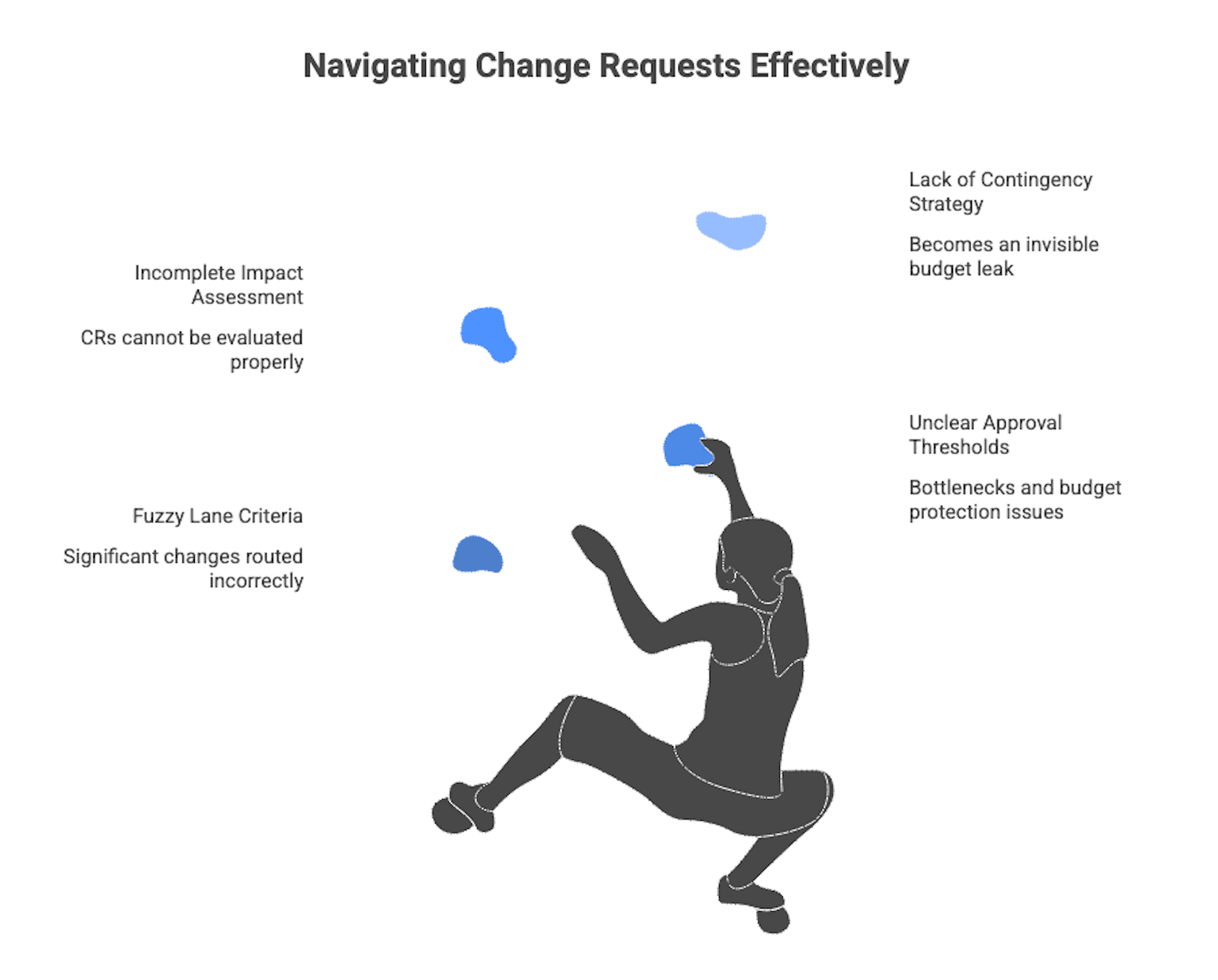

Prevention playbook: set guardrails before the next change lands

Prevention is not about saying no to change. It is about putting changes through a consistent path so trade offs are explicit and budget protected.

Establish a change control “fast lane” and “slow lane”

Create two lanes based on effort and risk.

Fast lane is for low effort, low risk changes that fit within clear thresholds and do not touch core workflows, integrations, or security.

Slow lane is for anything that could alter scope, milestones, or budget, or that touches critical areas such as roles, permissions, data, integrations, or performance.

Define the lane criteria in writing. If the criteria are fuzzy, teams will route significant changes through the fast lane and you lose control.

Set approval thresholds (who can approve what)

Approval thresholds prevent bottlenecks while protecting budget. Keep them tiered and explicit.

Below is an example matrix you can adapt. Use the same thresholds for both the client and vendor sides so the approval path is predictable.

Change size and risk | Typical examples | Required approvals | Notes |

| Fast lane, low risk | copy changes, small UI adjustments, simple config | Product Owner plus Vendor PM | Must stay within defined effort cap |

| Medium impact | new report, non critical workflow change, minor data adjustments | Product Owner plus Budget Owner | Requires impact assessment with schedule effect |

| High impact or high risk | new integration, role and permission changes, major workflow changes | Steering group plus Budget Owner plus Vendor Account Lead | Triggers re baselining if it changes milestones |

Make thresholds measurable where possible: effort cap, schedule shift, and risk triggers. Tie “high impact” to what the business cares about: milestones, compliance risk, and budget variance.

Require an impact assessment (in buyer language)

A CR that cannot be evaluated should not be approved. Standardize what “complete” looks like.

CR impact assessment template (minimum fields)

- Change description and business rationale

- Classification: scope change, refinement, defect

- Value: what outcome improves, and how you will know

- Cost: estimated effort range with assumptions

- Timeline impact: milestone shift or sequencing change

- Dependencies: systems, integrations, stakeholders, data

- Risks: security, performance, operational risk, rework risk

- Options: approve, defer, swap, split, or drop

- Funding path: contingency draw vs incremental budget

If estimates are single point numbers with no assumptions, confidence is low. Favor ranges and stated unknowns.

Build a contingency strategy (without hiding a slush fund)

Contingency is risk management. To keep it transparent:

- Document why contingency exists and what qualifies for use

- Log every draw as a change event tied to a CR

- Review draws regularly, alongside burn rate and forecast to complete

Separate “unknowns we expect” from “nice to have scope adds.” If contingency becomes a catch all, it turns into an invisible budget leak.

For a deeper budgeting view and cost drivers, see the related internal guide in the conclusion.

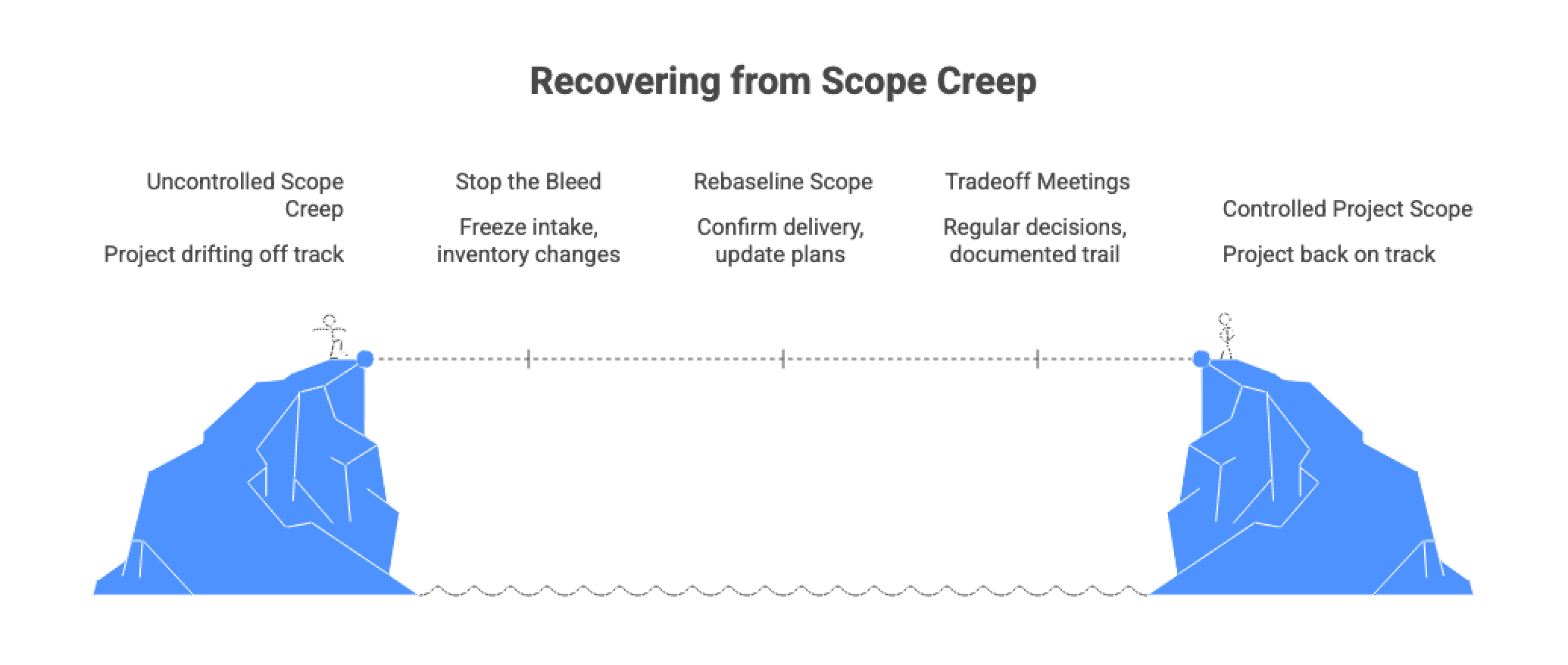

Recovery playbook: when scope creep is already happening

When the project is already drifting, your goal is to regain forecast accuracy without restarting the work.

Stop the bleed: freeze the intake (temporarily) and inventory changes

Temporarily freeze new scope intake while you build a clean inventory. You can continue executing already approved work. The freeze is about stopping new unassessed commitments.

Inventory sources to reconcile:

- Backlog and ticketing system

- Change log, if one exists

- Email and meeting notes where commitments were made

- Demo feedback lists and QA reopen reasons

For each item, capture: description, origin, classification, status, and an initial sizing guess. You are rebuilding traceability so you can re baseline credibly.

Re baseline scope and forecast (without restarting the project)

Re baselining is appropriate when approved changes make the original plan obsolete. Do not keep reporting against a baseline that no longer reflects reality.

A pragmatic re baseline sequence:

- Confirm what has been delivered and what is in progress

- Decide what stays in the new baseline vs what is deferred or dropped

- Update the backlog and release plan to reflect the new baseline

- Update the cost and schedule forecast tied to the revised scope

If the vendor resists formal re baselining after significant changes, budget surprises tend to continue.

Use a trade off meeting cadence (weekly or biweekly) to decide fast

A regular trade off meeting reduces side channel commitments and speeds decisions.

Agenda that works for finance and delivery:

- Review new requests and classify them

- Review impact assessments for pending CRs

- Decide using options: approve, defer, swap, split, drop

- Confirm what is in the next release

- Update forecast, contingency draws, and variance notes

The key output is a documented decision trail.

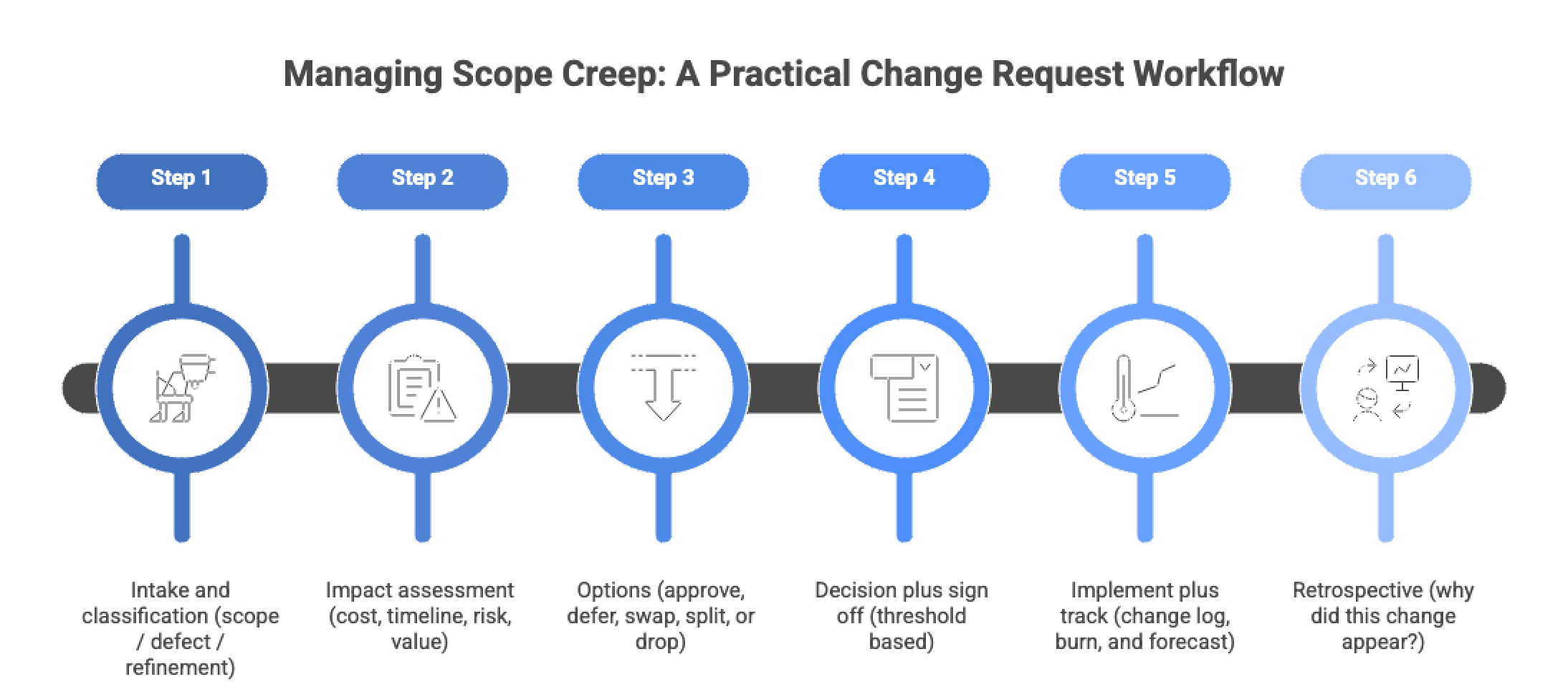

Change request workflow that protects budget

A consistent workflow is how scope control becomes real in day to day execution. Use this as the default path for all requests.

Step 1: Intake and classification (scope / defect / refinement)

Centralize intake. If changes can be requested in ten places, they will be.

Minimum intake fields:

- Request description and requester

- Link to baseline item or acceptance criteria

- Initial classification using the rubric

- Desired timing and business rationale

Enforce a rule: no implementation starts until the request exists in the system and is classified.

Step 2: Impact assessment (cost, timeline, risk, value)

Use the impact assessment template and require ranges where uncertainty is real. Include non functional implications and testing and release work.

If a change touches security, permissions, integrations, or data model, it belongs in the slow lane.

Step 3: Options (approve, defer, swap, split, or drop)

Do not let “approve” be the default. For significant changes, require at least two options:

- A minimal version now, full version later

- A scope swap, trading out a lower value item

- A defer decision with a clear revisit date

This keeps the budget conversation tied to value.

Step 4: Decision plus sign off (threshold based)

Tie sign off to the approval thresholds matrix and record:

- Approver names and roles

- Approved option

- Budget impact and funding source

- Schedule impact

- Any updated assumptions

If it is not signed off, it is not approved.

Step 5: Implement plus track (change log, burn, and forecast)

Your change log is the control tower. Track change volume and spend the same way you track baseline delivery.

Change log minimum fields checklist (track weekly)

- CR ID and title

- Classification

- Status: proposed, assessed, approved, in progress, done, rejected

- Effort estimate range and actuals

- Schedule impact

- Funding: contingency vs incremental

- Decision date and approver

- Release target

If a vendor cannot provide this visibility, you will not be able to manage the budget proactively.

Step 6: Retrospective (why did this change appear?)

Periodically review change origins and identify preventable drivers:

- Ambiguous requirements or missing acceptance criteria

- Missing stakeholder involvement during discovery

- Quality expectations not captured early

- Technical constraints discovered late

- Side channel decisions

The goal is reducing repeat causes and improving estimation accuracy over time.

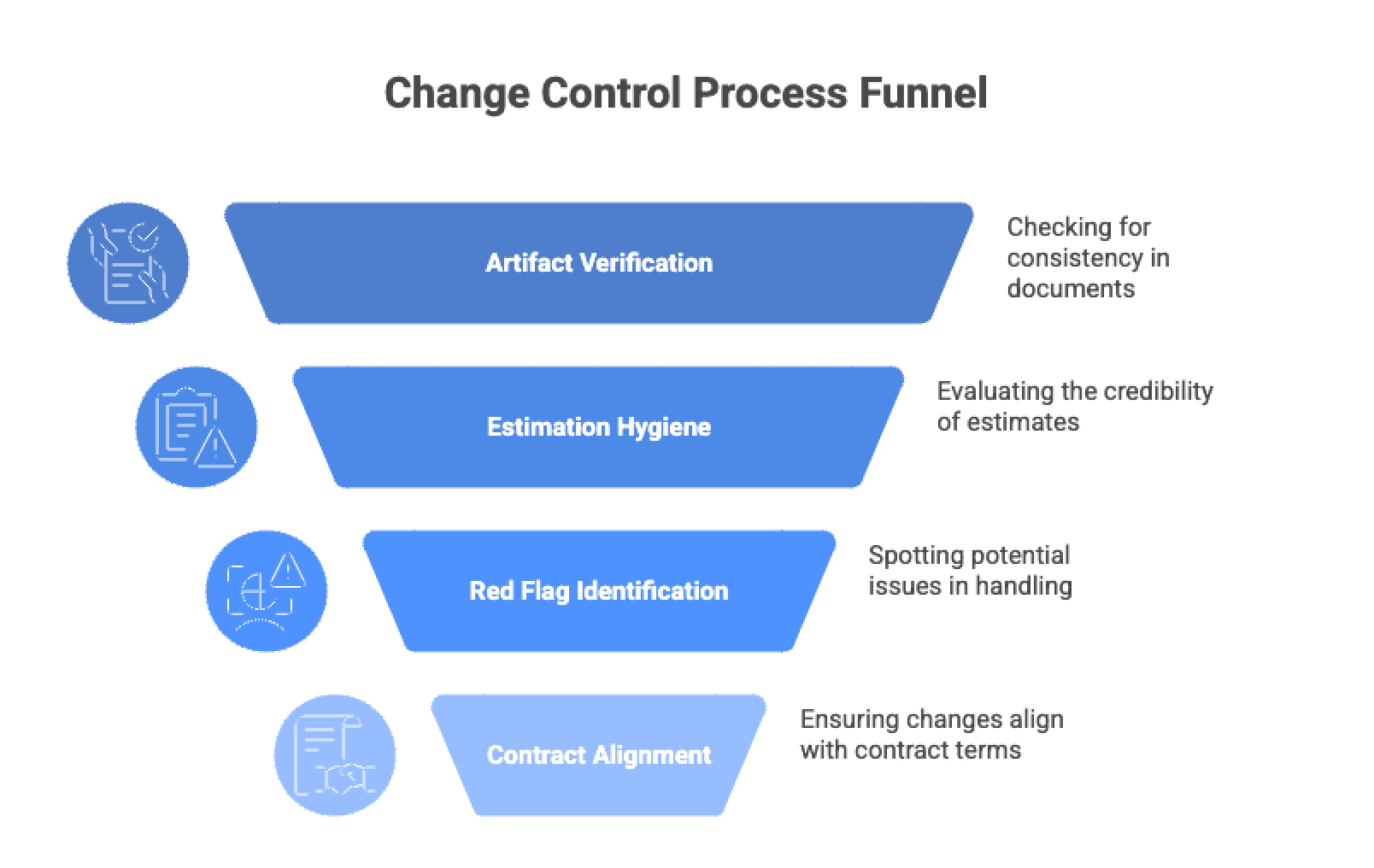

What to ask your vendor for

When vendor change control is mature, transparency is routine. Ask for artifacts.

Minimum artifacts: change log, impact assessments, updated backlog, release plan

Ask for these, at minimum:

- Change log with the fields above

- Impact assessments for approved changes

- Updated backlog reflecting approved decisions

- Release plan that shows what changed and why

Verification step: check internal consistency. Approved CRs should appear in the backlog and release plan, and forecasts should reflect them.

Estimation hygiene: how to judge whether numbers are credible

Credible estimates usually include:

- Clear assumptions and what is excluded

- Task breakdown that includes testing and release activities

- Ranges and confidence notes for uncertain work

- References to similar prior work, if available

A simple finance friendly test: ask what would change the estimate materially. If the vendor cannot name uncertainty drivers, the estimate is likely not well grounded.

Red flags in change handling

Watch for these patterns:

- “We will absorb it” as a repeated response without clear limits

- No maintained change log, or reluctance to share it

- Impact assessments that only mention development time

- Inconsistent classification of similar requests

- Frequent emergency changes driven by side channel commitments

These patterns often precede schedule slips, quality shortcuts, or delayed budget surprises.

How change control interacts with contracts

Contracts define the legal mechanism for changing scope and fees, often through CRs or change orders. Your operational workflow should align with that clause so approved changes are enforceable and audit friendly.

Contract model matters:

- Fixed price tends to tighten classification and push scope changes into formal CRs

- Time and Materials (T and M) offers flexibility but requires stronger governance to protect budget

- Hybrid models can work well when you define what is baseline and what is handled through a change budget envelope

For clause level depth and governance patterns, use the related contracts and governance guide linked below rather than expanding that content here.

Conclusion

A budget safe posture toward change means change is allowed, but never invisible. You keep agility by routing changes through a light workflow, making cost and schedule impacts explicit, and forcing trade offs when scope grows.

If you implement only one thing, implement the artifacts: baseline scope plus definition of done, a change log, and impact assessments with tiered approvals. Those three tools reduce most avoidable budget surprises.